Eaton boy battles hydrocephalus, sparks mother to start advocacy group to help

September 29, 2015 by PHF Filed under Uncategorized

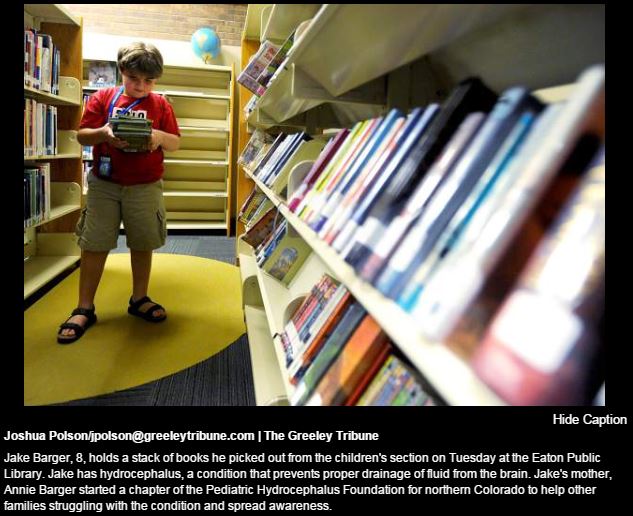

Jake Barger shakes his brown hair in front of his eyes at the Eaton Public Library as he talks about his favorite book series this week. It’s a tie between Magic Tree House and The Boxcar Children. He decides right then to write a crossover novel. The 8-year-old wants to be a judge, a doctor and at this moment, he’s decided to be a writer, too.

Jake’s mom, Annie Barger, watches proudly as her son chatters away about his plans. By now, he’s planning to bring The Avengers into his book. There might even be a movie deal, so he’s added director to his future resume. At this point, Annie’s eyes begin to tear up. Years ago, she didn’t know if Jake would have much of a future.

Annie was seven months pregnant with Jake when an ultrasound showed hydrocephalus in his developing brain. Hydrocephalus, or simply, fluid on the brain, is a birth defect, affecting one or two babies out of every thousand, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. There are multiple kinds of hydrocephalus, but in Jake’s case, one of the pathways in his brain where the natural fluid can drain is too narrow, causing it to build up. The Hydrocephalus Association estimates more than a million Americans live with the disorder. It’s the most common reason for brain surgery in children, according to the association. Jake’s first surgery, after all, came when he was 21 days old.

Jake was delivered via caesarean section at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora. The doctors told Annie and her husband, Paul, if he survived the delivery, he would be severely disabled all his life. After he was born, doctors told Paul they couldn’t believe they were looking at the same baby they’d been observing in utero. He was too responsive and energetic. Jake’s been surprising people ever since.

As well as Jake does, the defect still is a constant struggle. That’s why Annie started the northern Colorado chapter of the Pediatric Hydrocephalus Foundation. She’s in the process of organizing a fundraiser she hopes will take place by spring. The foundation raises money for hydrocephalus research and provides resources for those suffering from it, as well as education.

Annie’s main goal is to teach people what hydrocephalus is and how to properly handle emergency situations with people like her child.

“Being very vigilant and very proactive in advocating for your children is something that I do, maybe more than I need to, but it’s gotten us really far,” she said. “He’s the reason that we breathe.”

Jake’s had five surgeries. He has a shunt connecting the narrowing in his brain down to his stomach so the fluid can drain. The medical bills are endless, and so are the worries for Paul and Annie. They have to be hyper-vigilant. A headache or nausea could mean a shunt malfunction for Jake. If he complains of pain, or if he’s having trouble finishing his meals, Paul and Annie have a three-day rule — for the three days following the incident, Jake has to take it easy.

For Jake, a bad respiratory infection could cause an infection along the tube, which could be life threatening. Though he hasn’t had a seizure in years, another could always come. Even on a peaceful, happy morning, Annie fears what the afternoon might hold.

Another problem arises every time Jake steps out the door. Despite the commonness of hydrocephalus, not many know what it is or how to handle the disorder. Annie said she fights an uphill battle of education.

For example, once after a trip to the emergency room via an ambulance, a doctor insisted Jake showed symptoms of meningitis and wanted to give the boy a spinal tap. Because Jake’s fluid drainage is regulated by his shunt, a quick shift like that caused by a spinal tap could give him a stroke, Annie said. The doctor wouldn’t listen to her refusals and threatened to call child services if she wouldn’t let him get the procedure.

In school, Jake’s first-grade teacher exacerbated the behavioral issues that come with his disorder by refusing to listen to the medical reasoning or work with him on ways to improve. The hydrocephalus causes Jake to be a very linear thinker. He follows rules and does things as he is told. If he is told to use a blue marker to color a page one day, but then the next, he is told he can’t use that marker, he can get frustrated.

Some teachers were very understanding, though. Jake’s second grade teacher, Jen Delich, worked extensively with Jake to accommodate his needs and help him learn. Annie said she was incredible with him.

As Jake carried a big stack of Magic Tree House books to the front of the Eaton Public Library, Annie lagged behind, smiling as her boy struggled to balance the unwieldy load. He has no depth perception, but has learned to compensate for it, so it’s hardly noticeable. When he’s excited, he spins around in little circles, which he thankfully waited to do until the books were safely on the checkout counter. After the librarian scanned the barcodes and handed the heap back to Jake, he heaved them back into his little arms and hurried over to Annie to put them in the book bag.

“I’m training for American Ninja Warrior,” he said, flexing his little boy muscles.

Add it to the job list.

Editor’s note: This story has been edited from its original version to reflect the grade of one of Jake’s teachers.

Read more at: https://html.com/attributes/img-width/>

Read more at: https://html.com/attributes/img-width/>