PHF In The News: Colbert boy raising awareness about hydrocephalus

March 8, 2016 by PHF

Filed under Uncategorized

Comments Off on PHF In The News: Colbert boy raising awareness about hydrocephalus

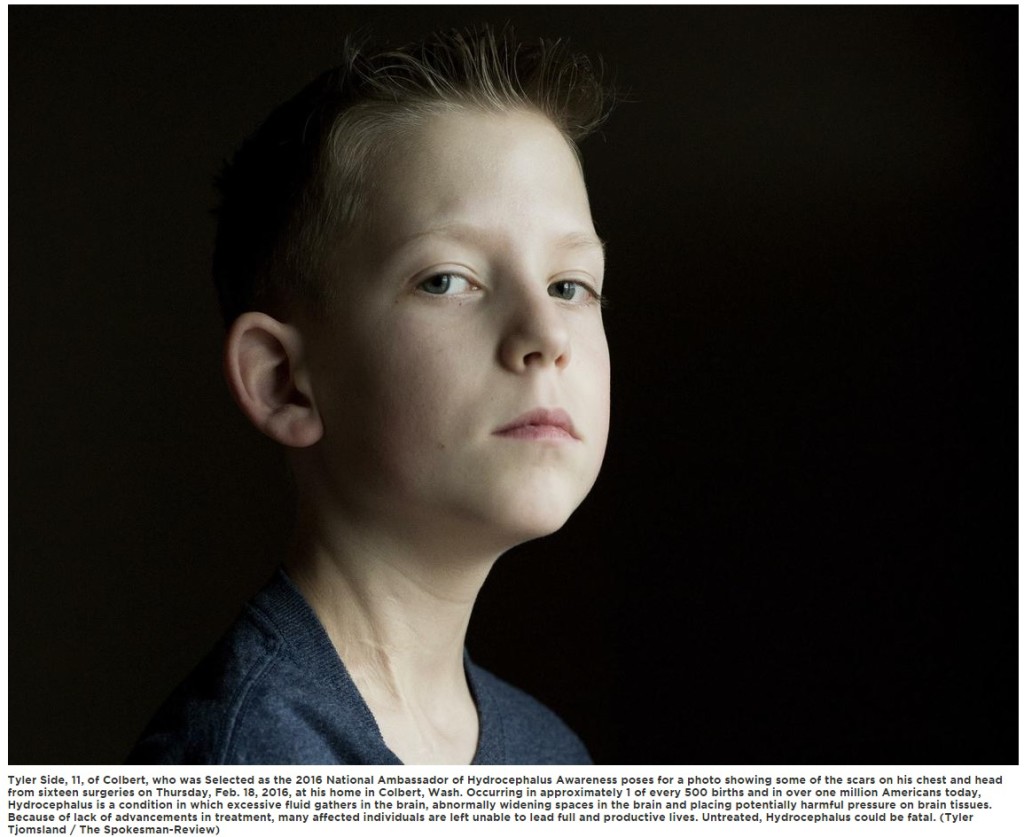

Tyler Side is a cheerful, social boy, who smiles often, but the 11-year-old’s scars reveal a childhood studded with struggle.

Tyler has hydrocephalus, an incurable brain condition characterized by excessive cerebrospinal fluid in the brain’s ventricles, which puts harmful pressure on the tissues of his brain. The scars are from the 16 life-saving surgeries the boy has endured due to the condition.

Now, the Colbert boy will use his story to help others with hydrocephalus. The Pediatric Hydrocephalus Foundation recently selected him as one of two 2016 national ambassadors for pediatric hydrocephalus awareness.

“I feel excited,” he said. “I hope that the hydrocephalus foundation can find a cure for it.”

Tyler will be featured in advertising campaigns and promotional materials heading into the eighth annual National Hydrocephalus Awareness Month in September. He and his family also will travel to Washington, D.C., for National Hydrocephalus Awareness Day on Capitol Hill in August.

So many uncertainties

Tyler was born at just 28 weeks gestation at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, where the Sides were stationed. The pregnancy had been healthy and normal, but placental abruption led to an emergency cesarean section and Tyler was born 11 weeks early, weighing a mere 2 pounds 12 ounces. He was rushed to the neonatal intensive care unit and hooked up to a ventilator.

For many days, doctors didn’t know if he would live. Imaging detected bleeding in his brain.

“It was scary,” said his mother, Crystal Side. “It was very traumatic.”

Despite the news, Side and her husband, Chris, remained hopeful that their baby would pull through, but they were uncertain what that would mean in the long run.

When there was no sign of increased bleeding, the family celebrated, although they learned Tyler might never walk or talk because of the damage.

At 20 days old, doctors diagnosed Tyler with post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus. The family was flown back to the U.S. by a military medical evacuation flight, still wondering what the diagnosis meant for their family and new baby.

“Would he be able to do the things other kids do? Would he be able to lead a full and productive life? There were just so many uncertainties,” Side said. “It was really difficult as a first-time parent.”

Tyler would go on to have numerous surgeries in his first 10 weeks of life, including a bowel resection following a diagnosis of necrotizing enterocolitis, and the family endured many days in the NICU, hoping Tyler’s progress wouldn’t be set back by more surgeries or infections.

Although he is walking and talking today, Tyler is unable to do many of the physical activities kids his age do because of the condition and the risk of injury. He and his family were ecstatic to learn he was selected to represent the cause – an activity they could give a resounding “yes” to. Side said she hopes her son will see that there are other children like him.

“Having him be able to connect with them will be really special,” she said.

More awareness needed

The causes of hydrocephalus are still not well understood. More awareness is needed, as well as better federal funding for research, said Michael Illinois, vice president and national director of advocacy for the Pediatric Hydrocephalus Foundation.

“Our goal is to provide funding to find better treatment options or help modify or update the current treatment options, while having an eye on one day finding a cure,” he said.

To treat hydrocephalus, a neurosurgeon typically places a shunt system in the body to redirect excessive fluid to other parts of the body, where it is reabsorbed.

Shunts are imperfect systems, and complications – mechanical failure, infections, obstructions, or the need to lengthen or replace the catheter – can result in more surgery, according to the National Institute of Brain Disorders and Stroke.

The condition can be congenital or acquired. Symptoms vary depending on factors such as age and disease progression. In infants, a rapidly increasing skull size is a sign of hydrocephalus, as well as vomiting, sleepiness, irritability and seizures.

The disorder occurs in up to 1 in 500 births and affects 1 million Americans.

Untreated, hydrocephalus can be fatal, and despite medical advances, many with the condition remain unable to lead full and productive lives, according to the foundation.

The all-volunteer nonprofit foundation advocates on behalf of members while working with policy makers at state and federal levels to push for more research and support in the fight against hydrocephalus.

It has 30 state chapters, including in Washington. Since 2010, it has awarded $375,000 in grants and donations to hospital and research centers around the nation.

‘It’s been a long journey’

Despite the challenges he has faced, Tyler has “such a great personality,” his mother said.

“Tyler is such a happy kid and always so pleasant,” she said. “All of his friends, teachers, everyone just loves him.”

She said, “it’s just amazing how well he’s doing.”

“He’s done great,” she said. “It’s been a long journey on some things. To look at him today, most people would never know that he’s been through what he has.”

11-Year-Old Tyler Side From Washington State Selected as 2016 National Ambassador of Hydrocephalus Awareness for Incurable Brain Condition

January 31, 2016 by PHF

Filed under Uncategorized

Comments Off on 11-Year-Old Tyler Side From Washington State Selected as 2016 National Ambassador of Hydrocephalus Awareness for Incurable Brain Condition

11-Year-Old Tyler Side From Washington State Selected as 2016

National Ambassador of Hydrocephalus Awareness for Incurable Brain Condition

Up until the night Tyler was born, my pregnancy had gone perfectly and we didn’t have any reason to suspect that the remaining 11.5 weeks would be any different that the first 28.5 weeks had been. At the time, my husband and I were stationed at Ramstein Air Force Base in Germany, away from family and friends, but embracing the culture and travel that being stationed overseas offered. After a day at work and suddenly becoming ill, I agreed to go to the hospital thinking that I would just need fluids to combat what I thought might be the flu. Little did I know that night would change our family’s lives and prove to be one of the most emotional rides we’ve ever been on.

Tyler was born at 28.5 weeks gestation on January 28, 2005 in Landstuhl, Germany due to placental abruption resulting in an unplanned emergency C-section. At 2 pounds 12 ounces, he was rushed to the NICU to be ventilated and for many days his survival was not certain. Early ultrasounds showed that Tyler had a Grade 2 and Grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage and we were devastated when the doctor told us that any further evidence of bleeding in his brain would mean that there was nothing else they could do for him. In the days that followed, we were hopeful that Tyler would pull through but uncertain what that would eventually mean.

Tyler was born at 28.5 weeks gestation on January 28, 2005 in Landstuhl, Germany due to placental abruption resulting in an unplanned emergency C-section. At 2 pounds 12 ounces, he was rushed to the NICU to be ventilated and for many days his survival was not certain. Early ultrasounds showed that Tyler had a Grade 2 and Grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage and we were devastated when the doctor told us that any further evidence of bleeding in his brain would mean that there was nothing else they could do for him. In the days that followed, we were hopeful that Tyler would pull through but uncertain what that would eventually mean.

When there were no additional signs of increased bleeding in his brain, we celebrated but were told that due to the damage, Tyler may never walk or talk, and though the bleeding had stopped, he was not nearly out of the woods. A few days later, at twenty days old, we received news that Tyler had post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus and at the time had no idea what this meant or how it would affect our precious baby. Since we were still at the military hospital in Germany, we didn’t have access to a pediatric neurosurgeon and were faced with a choice to be transferred to an off-base German hospital or sent back to Bethesda Maryland where he could be treated. We chose the latter and with short notice were moving across the world on a military medical evacuation flight to the National Naval Medical Center. To say that Tyler’s first month of his life was a whirlwind would be an understatement, but we would soon find that the ups and downs had only just begun.

Arriving in Maryland, we were thankful to be stateside, but were still far from our family in Washington State (though we did have quite a few visitors to see our miracle baby!) Tyler’s first shunt was placed externally and it pained us to continue to see him connected to so many tubes, though it did help relieve the pressure which had caused him so much discomfort. Unfortunately, that surgery would be the first of many as Tyler ended up needing a second, third, fourth and fifth external shunt all within 10 weeks. We struggled knowing that the surgeries were necessary but knew that every time the doctors would have to operate, the risk of the shunt failing continued to increase as the white blood cells rushed to heal the site where it could easily clog the catheters meant to help him.

Our next obstacle came when Tyler was diagnosed with necrotizing enterocolitis, and he had to have a large section of his bowel removed. This was another setback in his healing, and we were again filled with questions, worry, and doubt. We often felt so unprepared and spent countless hours and days in the NICU sitting beside Tyler’s bed just hoping and praying that the progress he made each day would not continue to be set back by surgery, infection, and uncertainty.

At just over 3 months in the Bethesda, we were again transferred to another hospital, this time moving to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia where Tyler’s shunt would be internalized. While this seemed to be a promising next step, it took a couple tries as the first shunt, a ventricular peritoneal shunt failed due to the scar tissue from the bowel resection. Much to our dismay, the next location that was chosen for Tyler’s shunt placement was through his jugular vein and into his heart, a ventricular atrial shunt.

Nothing seemed scarier, at the time, then knowing that the surgeons were going to feed the catheter through Tyler’s jugular vein toward his heart and have his body absorb the fluid in his bloodstream! Especially in such a tiny body, it seemed impossible that this option would work. However, on May 24, 2005, after nearly 4 months in the NICU, Tyler was finally able to come home!! He had undergone seven shunt surgeries and one bowel resection, but we were elated to finally be leaving the hospital. Being first time parents, we were paranoid about who he was around, if people had washed their hands before holding him, and where he may be exposed to germs, and having him just come home from the hospital after a roller coaster ride his first four months, we were even more paranoid! While the shunt did work for a short time, we did end up in the hospital four more times for shunt revisions in 2005.

Thankfully, however, in 2006, 2007, and 2008, Tyler only needed one revision each year, the last of which was to change the location of his shunt to be a ventricular pleural shunt. During his 2008 surgery, I can clearly remember the pediatric neurosurgeon coming to speak with us after the surgery with a concerned look. The surgery had taken much longer than normal, and the neurosurgeon had described the new location as having to ‘get creative’ in deciding where to go since the many revisions he already had used the most common shunt locations. Thankfully, the new placement was a success and since September 2008, Tyler has only had to have two more revisions, the most recent of which was in July 2014. To date, Tyler’s hydrocephalus has resulted in 16 surgeries so far, and like most parents of a child with hydrocephalus, the next possible shunt failure and surgery is always in the back of your mind.

Anyone that has met Tyler will say he is the sweetest and most charming boy. And any early doubts about his ability to walk or talk were proved wrong as Tyler worked through speech, occupational, and physical therapy to meet major milestones. The resilience and strength Tyler has shown in light of all that he has been through has taught us so much about life and perseverance. At ten (nearly eleven he reminds me), Tyler says he wants to be a doctor when he grows up and he loves riding his bike and scooter, skateboarding, playing video games with his friends, and listening to music.

When I asked him how he feels about having hydrocephalus, he said that sometimes he’s scared and sometimes he is just sad. He’s scared because he doesn’t know when his shunt is going to stop working and it makes him sad that he can’t play soccer like some of the other kids since he can’t get hit in the head. He said, “Being a kid with hydrocephalus is scary because the doctors have to cut into your head to find out what is wrong with your shunt.” But he followed this by saying, “but once, they’re done, then you feel much better.”

We are forever thankful to all of our family, friends, teachers, and medical staff who continue to show such support for Tyler and all he has been through. We are hopeful that with continued research we can improve the technology being used to treat this condition and eventually find a cure!

Read more at: https://html.com/attributes/img-width/>

Read more at: https://html.com/attributes/img-width/>